Ontology Modeling

- Modeling dependencies

- Basic modeling patterns

- Modeling methodology

- Result

Modeling dependencies

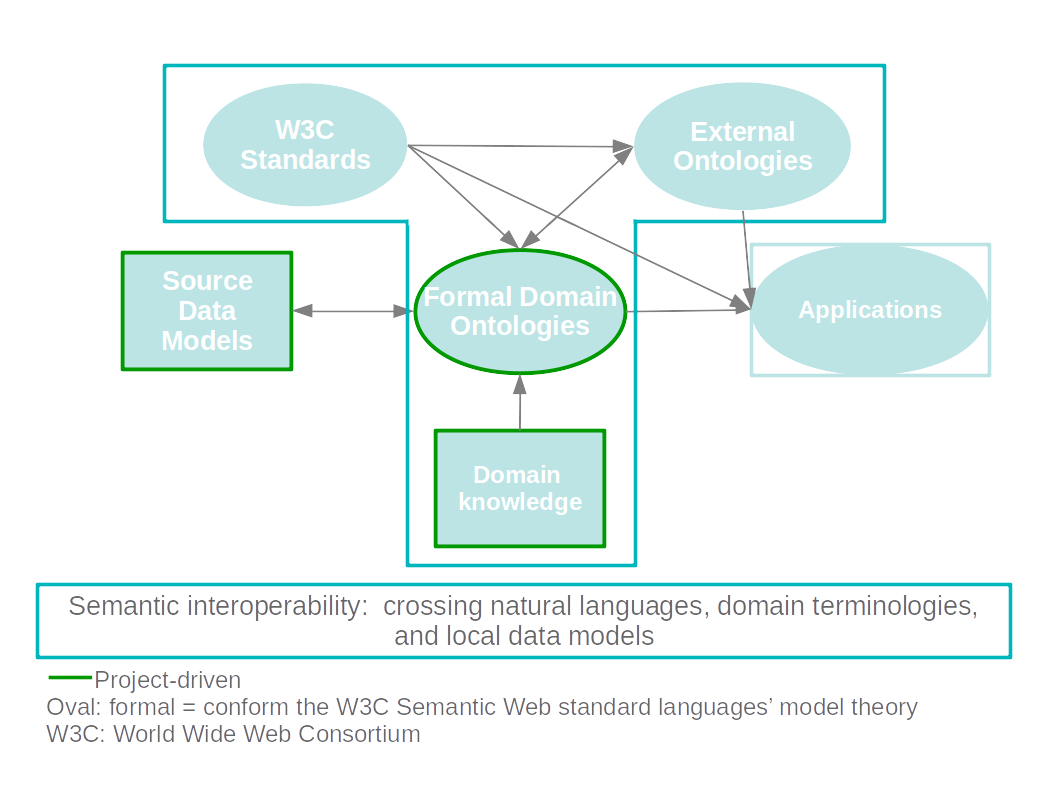

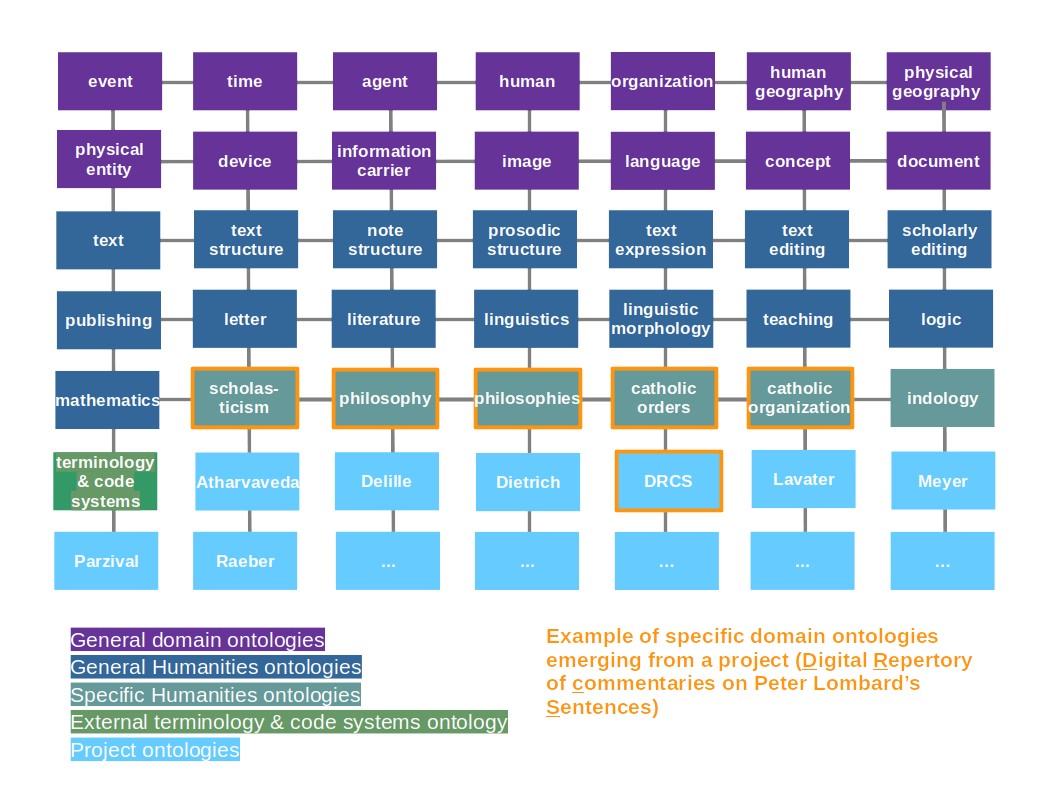

There are a series of resources that directly influence the modeling of ontologies (Figure 1).

Foundational W3C ontologies

Directive are the foundational ontologies of the W3C Semantic Web standard languages.

Using these brings standardization of syntax and basic semantics, and built-in logic, making ontologies and data machine interpretable.

External ontologies

When modeling for a certain domain, one does not have to start from scratch. The longer the SW is among us, the more likely someone else already created an ontology to cover needed semantics, possibly partially, often declaring more generic concepts.

There is a variety of existing ontologies. Some are very generic, others are quite specific. Some have become a de facto standard, e.g. SKOS and DC Elements, or practically are, e.g. Geo.

We use, i.e. base on following ontologies.

SKOS and DC Terms are mainly for ontology description purpose.

Geo, FOAF, Schema.org, SWEET, and mainly the more Humanities oriented CIDOC-CRM and FRBRoo (depending on the former) are used to base on.

Especially more generic domain ontologies will enable semantic interoperability.

Both the W3C and the external ontologies require a study, to really know their semantics.

Source data models

The input dependency is represented by the original data model, in the humanities most likely in XML, less often in SQL.

E.g. We support eleven projects with different databases. 7 have XML, 3 SQL and 1 has both.

For an ontology modeler, if not the researcher and/or the IT developer, to know another’s source data model requires repeated discussions on the precise semantics.

Domain kowledge

Last but not least, there is a dependency on the tacit knowledge of the domain specialists in the edition projects, needed for the implementation of domain knowledge to complement the restricted database models. To uncover this knowledge, a commitment on the part of domain specialists is needed, in order to reach consensus on semantics that often goes to a certain extent beyond their own specific research objectives.

All these dependencies represent a certain challenge and, initially, a substantial overhead.

But the ROI is big, and will be even bigger the more source data models are formalized along SWT, because this formalization will also contribute to the more general, cross-project semantics, preventing modeling the same concepts for new projects multiple times. Reaching a wide consensus on domain terminology (at the best on an international scale) further contributes to the semantic interoperability.

Basic modeling patterns

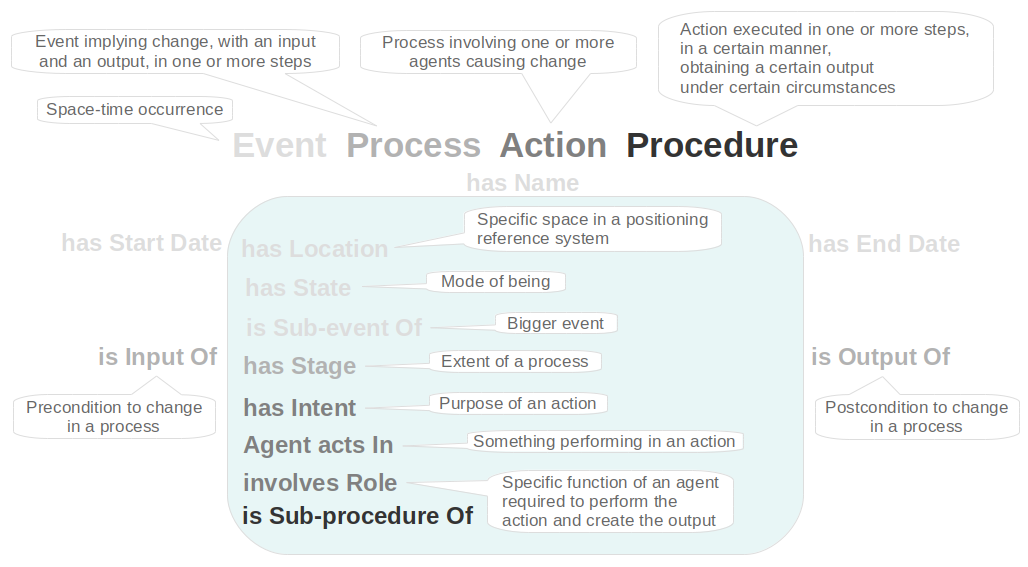

Modeling already starts before declaring an ontology, by conceiving or adopting basic modeling patterns that will be abundantly used in ontologies and data. Such patterns comprise a group of basic concepts and the relations (properties) between them. Examples of such patterns are ‘event’, ‘agent-role’, and ‘referencing’.

‘Event’ and its consecutively derived concepts ‘process’, ’action’, and ‘procedure’ (Figure 2) are four-dimensional entities described in time with start and end date, and space with location having geographic coordinates, name and code. Through the derived concepts the pattern becomes more complex, having input, output, and stage in a process, and having intent, agents (a person, organization, or even software) and roles in an action. The concepts are described in the figure.

For science, and especially in the humanities for historical research, it is essential that data are positioned in time and space. This includes calendar notation. Even crude time indicators, often at hand when dealing with information of the ancient times, can be used.

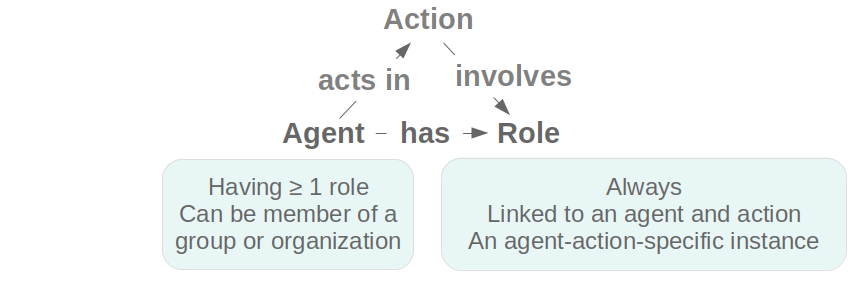

The concept ‘procedure’ enables to clearly distinguish between e.g. an edition as a procedure (editing) and an edition as a resulting product, therefore well suited for describing scientific editing as a variety of procedures, involving agents with different roles, and having a variety of in- and outputs. Figure 3 shows the agent-role pattern and the relations to the ‘action’ pattern.

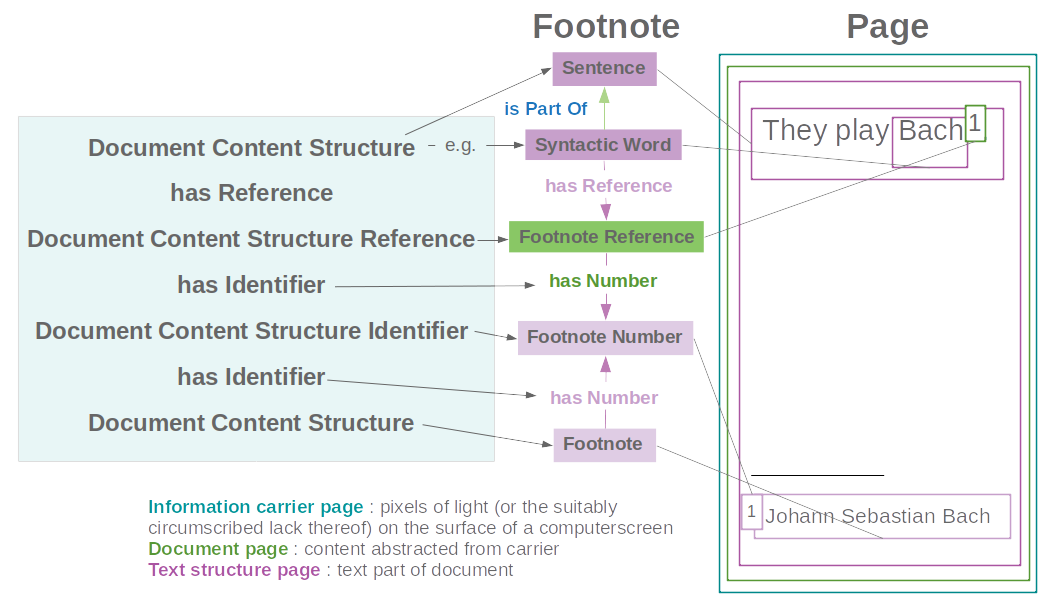

The basic modeling pattern for ‘referencing’ with ‘footnote’ as an example is shown in Figure 4. Other examples of application of the pattern are ‘endnote’ and citation source reference.

Modeling methodology

These formal semantic models are expressed in RDF/RDFS 1.1 and OWL 2 Full using their respective ontologies, and are developed in Turtle syntax.

Their development is in the GitHub project.

The authoritative files are open source and published on this website in the ontology library.

The ontologies are directly accessible (dereferenceable) with their namespace IRI.

Development tools

Ontologies, and also SPARQL queries and N3-rules, are created with the text editor Sublime Text and plug-ins, and tested on syntax and logic consistency with the open source EYE machine reasoner (De Roo 2020; see also N3-rule-based machine reasoning) and the editor Protégé (Stanford University 2020). The latter is particularly useful for offering a quick overview of merged ontologies to detect logical flaws, e.g. in subsumption or sub-property relations, or semantic shortcuts (gaps).

A Multitude of networked namespaces

In creating a semantic space for broad applicability, also ontology size and consequently the number of ontologies developed matter. Having “all contained in one” or even a few very big ontologies is rather difficult if the envisioned research space to talk about is broad, implying multiple domains. A basic approach is a multitude of networked namespaces, a web of highly interdependent ontologies (Figure 5). They differ in size, granularity and specificity.

A scientific project always needs general concepts such as ‘person’, ‘document’, text’, ‘image’, reusing elements from more general ontologies. A project ontology can exist, but should base on the general ones, and only contain project-specific elements, e.g. the concept of “Dreissiger” (set of about 30 verses) used in the Parzival-project.

Delineation and Naming

One of the bigger challenges, emerging from previous topic is how to partition knowledge over different namespaces, in other words to choose a workable delineation and hence name along the content (domain of discours) of an ontology. Another basic approach in this procedure, enabled by this choice, is easy addition and extension, and minimize the need for later splitting of an ontology. On the other hand some domain knowledge gets outdated, other updated, but it is expected in the humanities for knowledge not to change as fast as in natural sciences, hence a lower risk for deprecation of ontological elements.

Consensus

The ontology development evolves in a very iterative way, requiring the connection of different roles and kinds of expertise. It is very important to have regular discussions between modelers (4 in NIE-INE) and contact persons for edition projects (5), as well as with project domain specialists (12), since it is impossible to capture the needed project semantics all at once. ° Achieving consensus on domain semantics on different semantic levels, but also different group levels requires time, but is essential for enabling semantic interoperability. NIE-INE* operates in this process as a mediator within projects, but especially across projects, making modeling a very collaborative and multidisciplinary activity.

Structure and identification

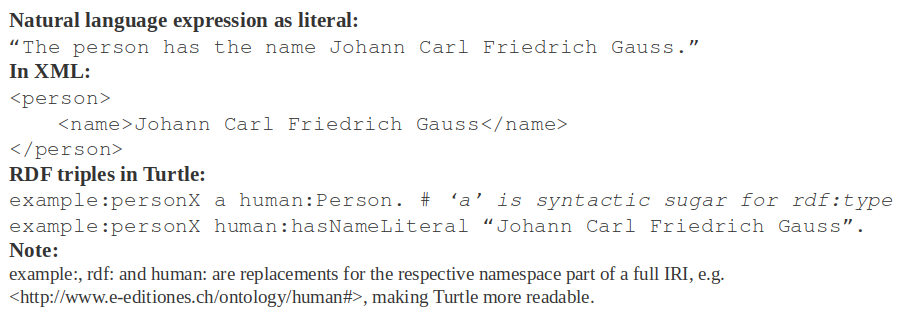

The basic expression unit structure in SWT is the triple, consisting of a subject, a property (or predicate), and an object.

SUBJECT PREDICATE OBJECT.

S P O.

personX hasFamilyName "Gauss".

The element in any position can be an IRI. The subject can also be a list (N3-rules), a plain or typed literal value, an anonymous resource (blank node), or a variable (SPARQL query, N3-rule). The property can also be a blank node or a variable. The object can also be a plain or typed literal value, a blank node or a variable.

A set of triples makes a graph, hence an OWL-ontology, RDF-data, the result of SPARQL querying, and an N3-rule are all graphs.

Figure 6 shows an example of such an identification and serialization in RDF triples converted from a sentence in natural language and encoded in XML.

Explicit statements

Since the W3C OWL ontologies contain the built-in logic of the RDF model theory, they are machine interpretable. When basing an own ontology on these, its elements have to be declared in an explicit way, with the least hidden assumptions, to keep them machine interpretable. Being explicit also represents a good way to reveal flaws in the original or formal data model. It is important to point out that this process introducing standards and being explicit is not leading to loss of expressiveness of data. On the contrary, RDF permits even co-existence of distinctive expressions of domain knowledge, as long as they are made explicit. For human development and usage, ontologies and ontological elements obtain clear multilingual labels and a description. We think it is important to keep the latter concise because the longer it is the more it tends to leave room for interpretation, instead of clarifying meaning.

Reification and abstraction

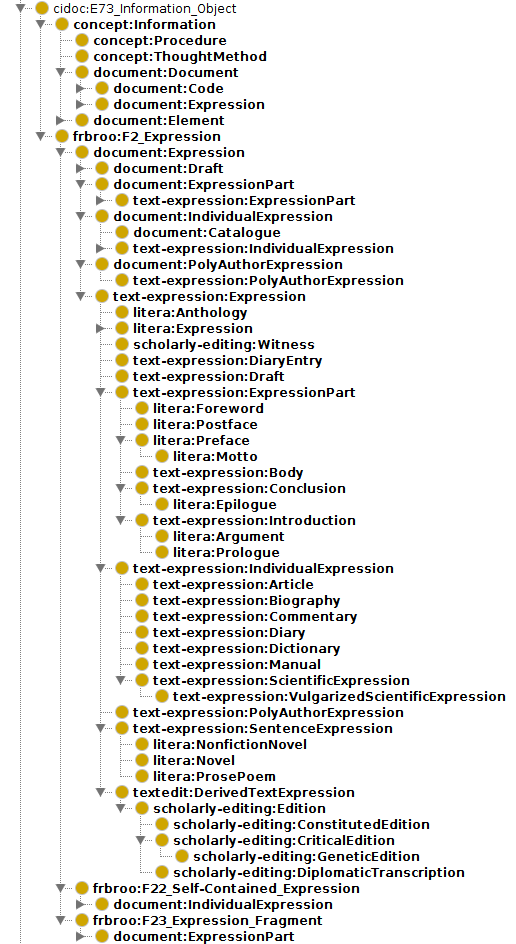

CIDOC-CRM and FRBRoo come with extra levels of abstraction and reification. Examples of reification are the class cidoc:E41_Appellation and the subclass cidoc:E44_Place_Appellation. An instance of the latter has an IRI – that is, it is a thing, not a string – which in turn has a name as a literal string value, e.g. “Lausanne”. Similarly all instances of the class cidoc:E33_Linguistic_Object have an IRI which in turn are linked to literal expressions. Examples of abstraction levels are the basic classes frbroo:F1_Work, frbroo:F2_Expression, frbroo:F4_Manifestation_Singleton, and frbroo:Item.

Building further on these FRBRoo classes, in the NIE-INE ontologies there are e.g. four different classes dealing with “page”:

1. information-carrier:Page: a physical surface of a leaf, e.g. in a manuscript or a book;

2. document:Page: a content structure with information, e.g. text lines and graphs, as part of a document expression, on an information carrier page;

3. text-structure:Page: text structure as part of a document page and a text expression;

4. text-editing:Page: text page of a scientific edition.

Middle-out

Adhering to the principles “As simple as possible, as complex as needed” and “The least ontological commitment” (i.e. providing the necessary and sufficient semantics), the modeling faces a challenge in finding the right balance between ground elements and details. Deep grounding is provided by very basic or upper ontologies, e.g. CIDOC-CRM. On the other end of the spectrum, there is the rather ad hoc project-specific modeling in a stand-alone way, which is not useful for semantic interoperability. Middle-out modeling starts at some needed points of depth and detail in a way that allow to easily extend ontologies.

Property oriented

Entities obtain meaning in the way and to the extent they are related to other entities via properties. Databases often contain implicit, condensed or shortcut semantics. In order to be explicit, it is important that these semantics are unraveled, with the consequent need to add more properties. A simple example is the conversion of a name to a family name and a given name. Together with the previous modeling feature (multitude of namespaces), this one leads to a network or a web of OWL ontologies and RDF data graphs.

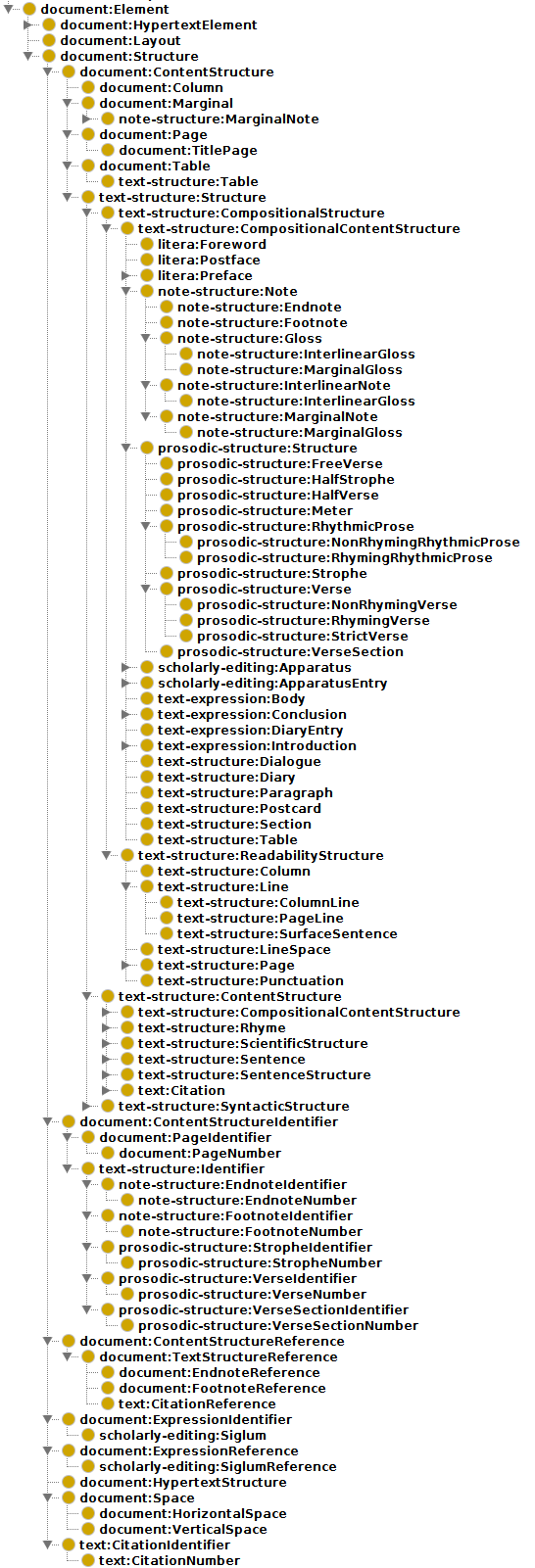

Result

There are 2 series: generic and project ontologies. The former are further divided into four levels: 1) general domain, 2) general humanities, 3) specific humanities, and 4) external terminology systems ontologies (Figure 1). This division is rather arbitrary, meaning that it isn’t formalized, but it is convenient to illustrate the articulation of ontologies and their interrelations.

The most populated ontologies are ‘human’, ‘information carrier’, ‘document’, ‘text’, ‘text-expression’, ‘text-structure’, ‘scholarly-editing’, ‘publishing’, ‘literature’, and ‘linguistic-morphology’. The ‘time’-ontology contains properties mainly for N3-rule declarations.

General domain ontologies

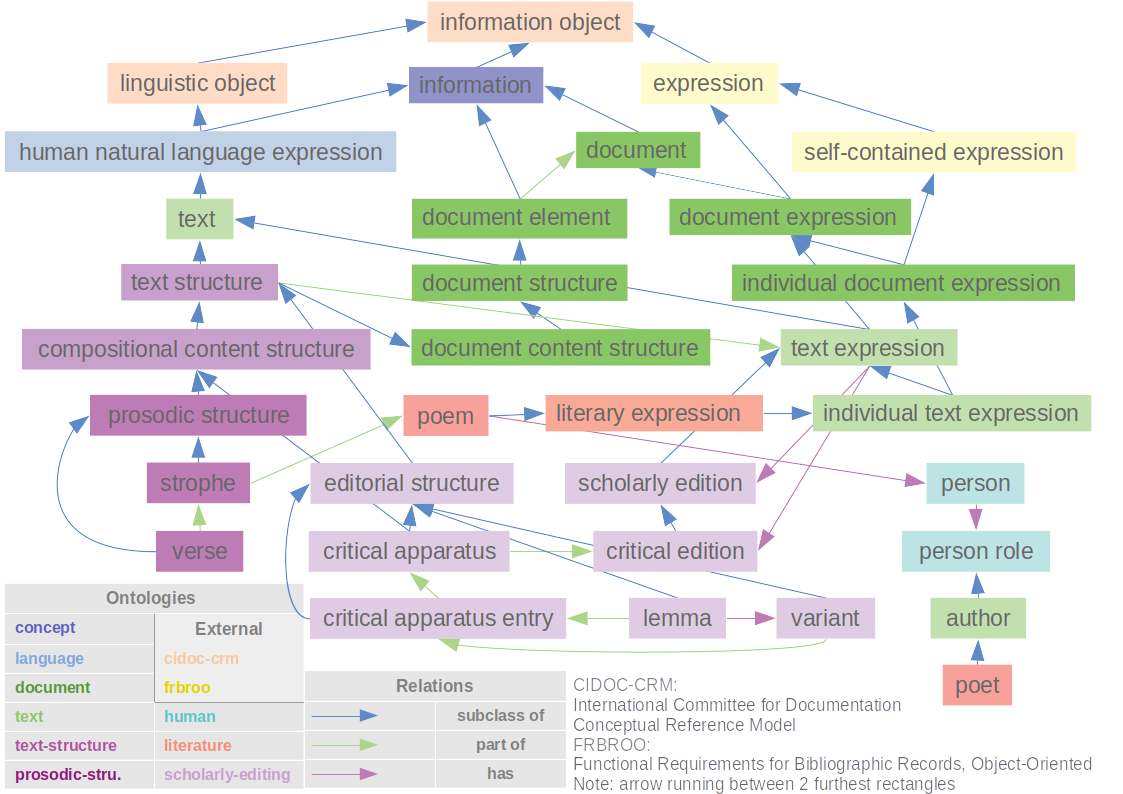

Although all ontological classes are instantiable, the more general ones will often function as “glue” to search in an RDF-database with SPARQL queries, and to enhance machine reasoning, e.g. for subsumption (subclassing). For example, if a scholar wants to search for all the languages in which a text is translated, the property ‘is translated into’ can be used without specifying the language. I.o.w. all instances of all subclasses of the class ‘human natural language’ are retrieved. In another case, one would like to find all information carriers (e.g. manuscripts and prints) bearing creations from of a certain author, but crossing more than one project: one project refers to prints existing in an archive and having a signature, and another project uses manuscripts preserved in a library with a manuscript identifier; both the manuscripts and prints can be found with a super-property ‘is on carrier’. As a general domain ontology, the concept-ontology (Figure 7 [TO DO]) describes for example concepts created by a person as abstract ideas, e.g. symbolic and propositional, basing on CIDOC-CRM and FRBRoo. It contains entities such as ‘information’, ‘identifier’, and ‘thought-method’, and their relations to each other and to other entities, e.g. persons. The document-ontology (Figure 8 and 9) describes documents, document structures, e.g. tables, identifiers and references, such as footnotes. It also contains the abstract document expression as based on FRBRoo, and different relations between document structures. FRBRoo provides for instance the concept of expression abstracted from its carrier.

General humanities ontologies

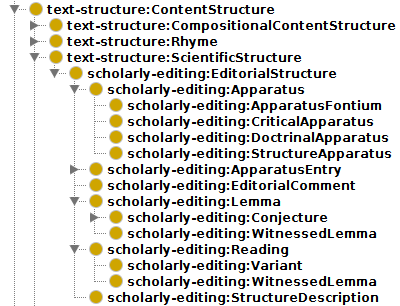

The “general humanities ontologies” comprise the core concepts for scholarly editions, as well as the bulk of common entities modeled so far in agreement with the edition projects. The following is a description of five core vocabularies for scientific editing in the humanities (Figure 8 and 9).

Text

This ontology describes text as a human natural language expression serialized in writable form. It contains all kinds of text forms (e.g. written, typewritten, transcribed, and printed) and roles of persons processing text (e.g. editor, annotator, and citer). It serves as basis for all text-related ontologies: text-expression, text-structure, text-editing, and literature ontology

Text expression

The eponymous core concept bases (via the document-ontology) on FRBRoo, as text abstracted from its carrier (Figure 9). The ontology declares further related roles (e.g. author and commentator) and general expression types (e.g. draft and commentary). It provides the basis for the literature- and scholarly-editing-ontology.

Text structure

This ontology describes all kinds of textual structures (Figure 10), e.g. syntactic, compositional, content, readability, and scientific (Figure 11). They form an upper layer to enable more flexible and extensive search, as well as machine reasoning. More specific entities are: word, sentence, paragraph, section, line, and text column. Extensions of this ontology are the prosodic-structure-ontology and the note-structure-ontology, containing entities such as verse and strophe, and marginal note and gloss respectively. An important relation between structures is ‘part of’, which, by its transitive nature, enables searching and machine reasoning in a way that do not require to explicitly state all possible relations between structures in the data, since they can be inferred via transitivity.

Text editing and scholarly editing

Both ontologies describe the necessary semantics for editing, the latter extending the former with specific scholarly entities, e.g. diplomatic transcription, critical edition, different types of apparatus, lemma, variant, editorial comment, witness, siglum and more alike. Also related roles are declared, e.g. editor, glossator, and critical text editor. An extensive set of properties relates these entities to each other, as well as to text, text structure and expression elements (Figure 8, 9, and 11).

Publishing

This ontology describes classes and properties related to publishing, e.g. publication and its subclasses, e.g. printed and web publication, serial like newspaper, periodical, or magazine. There is a substantial set of properties relating expressions and other entities to elements in this ontology.

Literature

This ontology describes literary genres such as narrative and different kinds of poetry, and further different types of literary expressions (e.g. poem, hymn, novel) and their subclasses. It also contains related roles, e.g. poet and novelist. Different types of literary structures are declared, e.g. foreword, preface, prologue, and epilogue, and related properties (Figure 8, 9, and 10).

Specific humanities ontologies

This series comprises more specific entities as used in different specialized domains in the humanities, e.g. about scholasticism. Some ontologies are an onset (e.g. ‘indology’, ‘catholic organization’ and ‘philosophy’), providing the more general concepts as needed for the current projects, but they can and will be extended. ‘catholic orders’ and ‘philosophies’ describe subclasses of classes in aforementioned ontologies, also to be extended. Although the scope of these ontologies is narrower, i.e. more project-oriented, the entities can be reused in another context, if applicable, meaning that they do not need to be restricted to a specific project.

External terminology and code systems ontology

This ontology contains formal descriptions of terminology and code systems and their datatypes, as link between such systems’ data and OWL-ontologies and RDF-data. Examples of terminology and code systems in the humanities are the Open Archives Initiative (OAI 2020), and the Gemeinsame Normdatei (GND) (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek 2020) for the DACH countries. A generic system is for example the hexadecimal color coding to describe e.g. text color. Other datatypes are declared in respective domain ontologies. Examples are calendar:julianDate in the calendar-ontology to type a Julian date literal, languages:iso639-2 in the languages-ontology to type ISO language standard codes, and text:characterSize in the text-ontology to type a numeral representing a character size.

Project ontologies

These ontologies contain entities only used in the respective projects, but they are still usable outside those projects, if applicable. E.g. the Parzival-ontology contains the concept of “Dreissiger”, being a set of about 30 verses, reusable in another project about the verse novel Parzival. All other more generic ontologies are to different degrees used in all project ontologies to create a subclass or subproperty from. Generally, another project about a same author could reuse some ontological elements in order to be linkable with one of the projects supported by NIE-INE. It then would be possible to query the two different SPARQL endpoints simultaneously, which is essential for research since the triple stores can contain complementary information on the same subject. This is actually the case for the DRCS project, dealing with the commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, which is linked to another project of the University of Baltimore, US. This case demonstrates the added value of semantic interoperability between disparate databases, facilitated by the use of the same external ontologies CIDOC-CRM and FRBRoo.

Atharvaveda

This ontology represents the formal description of specific concepts in the critical edition of the Paippalāda Recension of the Indian Atharvaveda, an anonymous collection of verse songs about everyday life (c. 1200-1000 BC). It contains subclasses and subproperties of elements in the text, text expression, text editing, prosodic structure, literature, and indology ontologies, modeling a sub-set of the Indian Veda literature.

Delille

Formal description of specific concepts in the scientific edition of the third canto of Jacques Delille’s (1738–1813) verse poem L’homme des champs (The Rural Philosopher). One of the main goals of the project is the reconstitution of the reception of Delille’s poetry. The main concepts are about the poetic expression and its structures, the works (e.g. anthologies, dictionaries, and articles) and their authors (and other roles) that cite verses of the canto, and the scientific commentaries on the citers and their works.

Dietrich

Formal description of specific concepts in the critical edition about father Joseph Dietrich’s monastery diary (1670-1704). The concepts are diary related. The majority of the semantics is expressed with the more generic ontologies. One of the main subjects of the diary is weather description.

DRCS

Formal description of specific concepts in the scientific study Digital Repertory of Commentaries on Peter Lombard’s Sentences (DRCS, Peter Lombard: c. 1096-1160). The project collected over 1700 commentaries, from which further data has been extracted such as the identification of the authors, their names and life dates, their membership in religious orders, their philosophical thinking and tradition, their roles in the editing processes (e.g. editor, abbreviator, corrector) along with all graspable information about the text itself, like genre, location and time of creation as well as its bibliographic information. The specific humanities ontologies containing those concepts are shown in Figure 5. The DRCS-ontology itself contains mainly the different types of commentaries and the Stegmueller related concepts. Interlinking this collected data through our ontologies provides highly dynamic possibilities of evaluating and detecting yet unknown patterns, interrelations and networks in medieval philosophy and intellectual history. The reception of texts and writers, thought patterns, writing traditions or thought methods can be detected and traced down through time.

Kuno Raeber

Formal description of specific concepts in the online publication of the lyric work of the Swiss poet Kuno Raeber (1922-1992). Being the first model as a project-ontology in the learning curve of NIE, it contains more than the average number of multi-parent subclasses. On the other hand there is also the need for single instance classes leading to a more extensive ontology than for other projects. The concepts are mainly about the different expression formats (written, typed etc.), their carriers and their convolutes, strongly representing the FRBRoo ontology.

Lavater

Formal description of specific concepts in the critical edition of correspondence of Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801). All concepts in this ontology are letter related, as subclasses of more generic classes, enabling to keep the internal structure close to other sources as for example e-manuscripta.ch.

Meyer

Formal description of specific concepts in the critical edition of the correspondence of Conrad Ferdinand Meyer (1825-1898). Also in this ontology all the concepts are letter related, as subclasses of more generic classes, and this on the level of expressions and information carriers.

Parzival

Formal description of specific concepts in the critical and digital edition of the verse novel Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach (c. 1160-c. 1220). These concepts are on one hand about a series of transcriptions (or parts) of the verse novel, on the level of expressions and information carriers. On the other hand the critical edition with different apparatus is described formally, using extensively the scholarly editing ontology.

Wölfflin

Formal description of specific concepts in the scientific study Heinrich Wölfflins gesammelte Werke (1864-1945). Due to the current absence of a consolidated source data model, the ontology is not published yet. However, it can be noted that most of the needed semantics is already covered in more generic ontologies.

The Kritische Robert Walser-Ausgabe (1878-1956) and the Anton Webern Gesamtausgabe (1883-1945) govern their own ontologies, with the intention to link to our ontologies in a later stage. Therefore, we already see to it that this will be possible.