Introduction to Semantic Web Technology

- Heterogeneity of digital data

- Data and their semantics for humans and machines

- W3C semantic web standards

- Some reflections

- Domain ontologies used in the humanities and publishing

Heterogeneity of digital data

In general a growing number of people produce in their activities, both professionally and leisurely, an ever faster growing amount of very heterogeneous digital data, resulting in a very complex information landscape.

This heterogeneity has several causes.

Humans have developed more than 7800 natural languages, each of them with more or less own interpretation and description models of the human observation of reality. Even when different languages belong to the same group, a 1-1 translation is often impossible.

Within a language, the way people describe things with a certain vocabulary or terminology or jargon differs along education, science, occupation, industry and other domains. But also intra-disciplinary terms not always bear exactly the same meaning.

On the technological side, a lot of data are little or not structured (free text). One can structure data through parsing the text, but unless the accuracy of text recognition is 100%, data errors are introduced. Creating possibilities to up-front input sufficiently structured data might be an easier, cheaper and more reliable approach. But even if data input is structured in databases (e.g. in XML or SQL), their schemas or data models, though capturing consented domain knowledge (as found in literature, or in tacit knowledge in the heads of domain specialists) are often localized# through natural language and personal representations such as abbreviations and cryptic naming and not fully described. In other words they are not always stating meaning explicitly.

Data and their semantics for humans and machines

In order to communicate within this growing amount of heterogeneous information, humans need another paradigm of the interoperability of computer systems to enable enhanced data linkability. Hyperlinking identified resources on the Web, e.g. a wiki-page or an application, is only one part of the story. Going to the content of the pages, the meaning of every resource (e.g. a document, a subject, an image) has to be known, i.e. described, in a way a machine can handle it, so that the resource is linkable in an automated way.

This paradigm emerges as a unifying standard language of logic to express the information’s semantics in such a way that it solves the aforementioned issues.

It is a tremendous advantage to escape from natural language translations and have a language with more basic semantics of logic and mathematics. It permits structuring information in a database with explicitly stated data models. And even as a standard, it will enable also the expression of subtle differences in terminologies, instead of needing to make the information landscape less complex by simplifying its semantics. The biggest advantage of such a language of logic is making its semantics machine interpretable. With this kind of artificial intelligence, new knowledge can be derived from existing one.

W3C semantic web standards

In 1990 at the onset of the World Wide Web (WWW), Tim Berners-Lee already envisioned a unifying language of logic. But it wasn’t until 2001 that the WWW Consortium (W3C) started the development of the Semantic Web (SW) aka Web 3.0, resulting in a set of open source technology standards. W3C is the international organization occupied with standardization of the technology driving the Web, also e.g. HTML and XML.

The SW standards enhance the interoperability of computer systems through the introduction of machine interpretable or formal semantics of natural language.

For clarity it has to be said that the novel element in the SW is not the semantics, but the Web. The development towards this Web can be explained shortly like this: First there was natural language and its semantics and later on logics of all kinds. Then there was Information Technology, the Internet connecting computers, and the Web connecting pages, documents and applications. And finally the SW environment with its standards is able to formalize the semantics of natural language and make it machine interpretable, which enables linking information resources in a meaningful way.

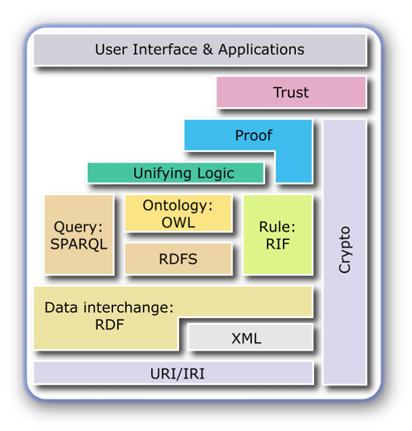

Figure 1 shows the common representation of the different technologies with their respective standards comprised in the SW stack.

Identify: IRI

The Web already comes with digital resources bearing an IRI or Internationalized Resource Identifier (URI or Uniform Resource Identifier and URL or Uniform Resource Locator are respective sub-concepts). # So, it is already good to know what resource an agent — person or machine — is speaking about because the former is identified, and if another agent looks for it, it can find it (if accessible). # The next step is for the other agent - person or machine — to understand what the resource is about. The fact that also the machine ‘understands’ content is the game changer. Therefore it needs explicit formal semantics based on logic. More precisely the different standard languages (except SPARQL) have their model (or interpretation) theory based on first order logic and set theory.

Formalize data, data models, and domain knowledge: languages of logic

Those languages are the Resource Description Framework (RDF), RDF Schema (RDFS) (W3C 2004-2), and the Web Ontology Language (OWL) (W3C 2012), having an increasing expressiveness, i.e. they can be used separately to express formal statements in a growing complexity.

RDF enables mere data expression, without declaring a model. RDFS already permits modeling a simple ontology, and OWL is meant for the declaration of a more complex ontology (or formal dictionary).

OWL itself has different grades of expressiveness with OWL 2 DL, OWL 2 Full and profiles as discussed in the W3C document. We use OWL 2 Full.

Some descriptions of ‘ontology’ in the SW are: “a conceptualization of a domain to enable knowledge sharing” (W3C 2009) and “a representation of terms and their interrelationships” (W3C 2004-1).

Ontologies and data can be serialized in Turtle (W3C 2014-1), RDF/XML (W3C 2014-2), or N-Triples (W3C 2014-3) syntax.

Query: SPARQL

SPARQL (W3C 2008) is the RDF query language, to retrieve data from an RDF graph database or triple store. It has its own syntax.

We use the open source Apache Jena Fuseki SPARQL server (Apache 2020).

Formalize the means to infer: rule

Rules are the means for inferring new data from data with machine reasoning. The Rule Interchange Format (RIF) Datatypes and Built-Ins 1.0 (W3C 2013) contains standard specifications.

Infer: unifying logic and machine reasoning

Unifying logic establishes consistency and correctness of data sets and permits to infer conclusions not explicitly stated but required by or consistent with a known set of data, by applying the rules with a machine reasoner having the logic implemented.

Proof: machine reasoning

Proof provides trace or explanation of the steps of logical reasoning and needs to be given by the reasoner.

Trust

A trust layer offers authentication of identity and evidence of the trustworthiness of data, services, and agents.

All but the last layer subjects are further discussed in separate sections.#

Focus on logic and machine reasoning

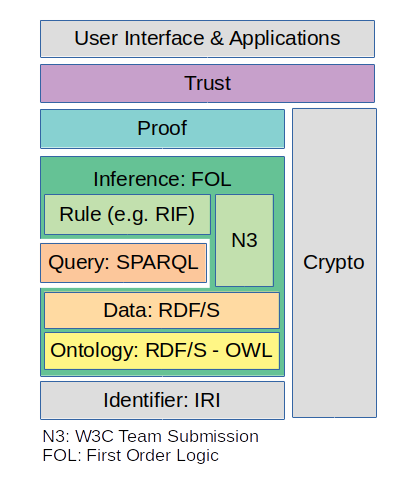

The author took the liberty to slightly change the previous graphic to the one in Figure 2 to emphasize the dependency on formal logic, and place ontologies at a basic level.

We always use RDF, RDFS, and OWL together without making the aforementioned distinctions. The figure shows the foundational ontologies of the three languages themselves together as the basis, arguing that even for the simplest data expression the RDF-ontology is needed. Once declaring domain knowledge in own ontologies, also elements of the RDFS- and OWL-ontology are needed.

From a formal model point of view we can describe an ontology further as a collection of classes (or sets, categories) and properties (or relations, predicates) between instances (individuals) of classes.

The next layer represents the formal data expressed using the ontologies.

Notation 3 language

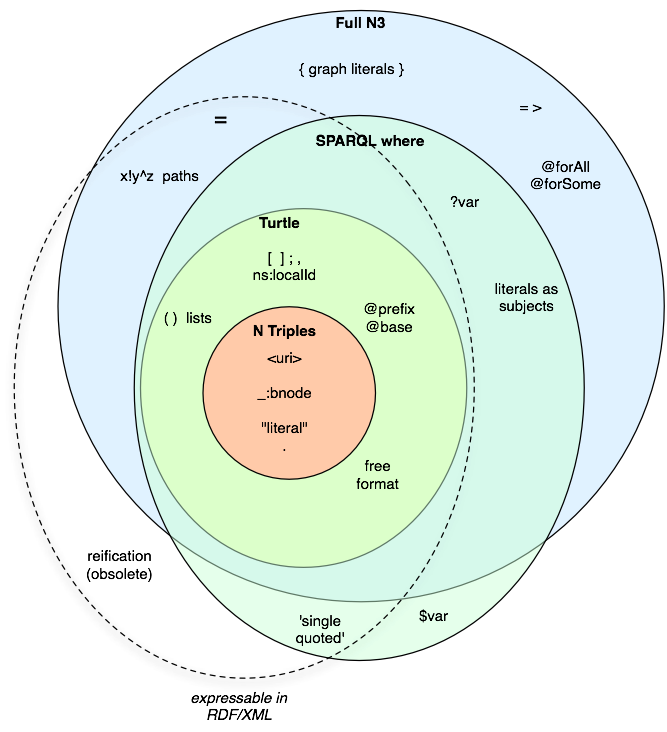

Notation 3 (N3) (W3C 2011) is an assertion and logic language which is a superset of RDF, and still a Team Submission, i.e. not a standard (or recommendation) yet. N3 extends the RDF datamodel by adding formulae (literals which are graphs themselves), variables, logical implication (‘if/then’; =>), and functional predicates, as well as providing a textual syntax (alternative to RDF/XML). Besides ontologies and data, it permits the declaration of inference N3-rules and N3-queries (see also N3-rule-based machine reasoning). In this way Turtle is a subset of N3, as N Triples is a subset of Turtle, as shown in Figure 3. The syntactical details are discussed in other chapters.#

Note: there is a W3C N3 community group to further develop N3 and bring it to a possible standard. Members are for example Tim Berners-Lee, Jos De Roo (the developer of the EYE reasoner). The development is in the GitHub W3C N3 repository.

Some reflections

RDF is more than ‘yet another data format’. Implementing the SW standards or RDF-izing data goes way beyond long-term data storage. Especially the effort to create and/or reuse necessary ontologies, providing a sound semantic space to express source data in a formal way, is substantial. In this sense RDF-izing benefits from departing from quick, ad hoc, standalone development, and aims at a fundamentally different data processing of which the data translation into RDF is only the beginning. Of course development complexity and time depend on the needed semantics to express data and solve academic, industrial or other data flow and research issues. On one hand an existing ontology and a limited set of rules can fulfill the requirements. On the other hand a library of new ontologies (mostly based on existing ones) and a series of rules sets have to be developed providing very different functionalities to solve all kinds of issues.

Modeling domain ontologies providing the required domain semantics is not a very common IT development activity. It can be pretty time-consuming, needing both width and depth. One can learn it by adopting certain best practices and efficiency, but different aspects need to be covered: semiotics, linguistics, formal logic, math, analysis, an eye for detail but also keeping an overview, and participation in conceptual discussions with domain specialists. Modeling is very iterative, likely taking a while until satisfying.

Domain ontologies used in the humanities and publishing

Note: not meant to be exhaustive.

- Generic ontologies:

- Natural science ontologies: also used in the humanities

- Humanities domain ontologies: